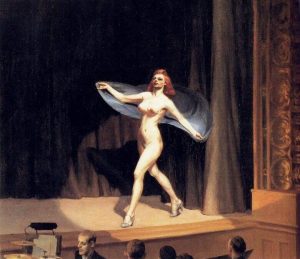

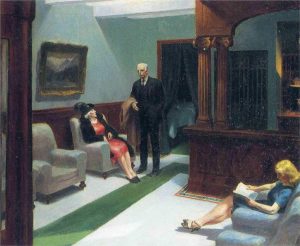

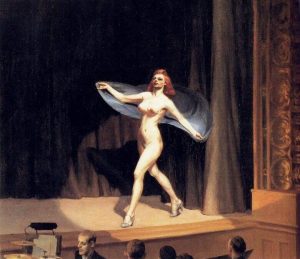

In “Girlie Show,” the setting of the story is never stated, but the painting used as the ekphrasis foundation was created in 1941 and based on the description of Pauline’s clothing on page 5 (dress, stockings, slip, brassiere, step-ins), it would be logical to assume that the setting is the same period. The 1940’s were a time when women were expected to strictly adhere to the role of the Good and Loyal Wife who obeyed their husband without complaint and provided ‘service with a smile.’ The protagonist, Pauline, spends 90% of the story on the receiving end of her husband’s emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. There are multiple signs that he is seeing other women (shoes that don’t fit her, staying out constantly, drawings that certainly do not look like her), yet Pauline continually chooses to ignore the evidence up until pages 12-13, when she happens to spot him out and about and she follows him to a theater. It is also on page 13 that Pauline meets her first true ally at the theater.

Mae approaches Pauline in a cordial manner and confirms that her husband is indeed a regular at the theater. Mae drives off a catcaller watching Pauline, then takes her backstage to prevent any similar happenings, at the same time protecting her from the remarks of the other performers they pass by. In Mae’s dressing room, Pauline nearly cries until she sees gifts from her husband to Mae. She no longer wants to cry; instead she feels rage bubble up inside of her. Mae helps Pauline transform into a dancer and gives her a brief time to perform onstage, to enact revenge on her unfaithful husband. The plan works and he is taken outside and beaten to a pulp by the bouncer, screaming blame at Pauline for his situation.

Mae approaches Pauline in a cordial manner and confirms that her husband is indeed a regular at the theater. Mae drives off a catcaller watching Pauline, then takes her backstage to prevent any similar happenings, at the same time protecting her from the remarks of the other performers they pass by. In Mae’s dressing room, Pauline nearly cries until she sees gifts from her husband to Mae. She no longer wants to cry; instead she feels rage bubble up inside of her. Mae helps Pauline transform into a dancer and gives her a brief time to perform onstage, to enact revenge on her unfaithful husband. The plan works and he is taken outside and beaten to a pulp by the bouncer, screaming blame at Pauline for his situation.

The automatic assumption in my mind while reading was that Pauline and Mae would have a catty, antagonistic relationship with each other upon the reveal about Pauline’s husband. I was pleasantly surprised and intrigued when they did not take that route. They instead established an immediate closeness. While they are together, Pauline recalls childhood memories that shine a more positive light on her life, like scarfing down forbidden candies with a female peer. It is incredibly apparent that Pauline feels far more comfortable with Mae than anyone else, namely by:

- Relaying the stolen candy story to Mae, despite never having told anyone before

- Noting Mae’s physical features

- Feeling bashful while Mae does her body makeup

- Outright flirting with each other

At the end of “Girlie Show,” after watching her husband be pummeled, Pauline returns to Mae’s dressing room, closes the door behind her, and, one would assume, furthers her already intimate relationship with Mae.

Pauline’s warranted rebellion and being around Mae was a breath of fresh air to walk through. More often than not, in fiction stories, there is a prominent aloneness for female protagonists. They must deal with personal struggles by themselves or at the least with a mother/sister figure to pat their back and offer reassurance. To witness women who barely know each other helping one another out purely out of sympathy or empathy is immeasurably gratifying. In our own world, women will help other women whether in small or large ways, whether by providing supplies in times of shortage (personal or familial) or taking information about unknown dates that they plan to go on or seeing someone who looks uncomfortable in a place/talking to someone and offering to accompany her. All of these establish unity between one another and a desire to protect the wellbeing of fellow women from all walks of life. I am so very glad that this was the path Megan Abbott took Pauline down.

While reading “The Truth About What Happened” by Lee Child, there were a few things that popped out at me (especially after reading “Soir Bleu” right before it). Some of these were very obvious, such as the author’s choice to use dialogue for the primary structure of the piece, but there were other details and interpretations that I personally experienced and would like to point out.

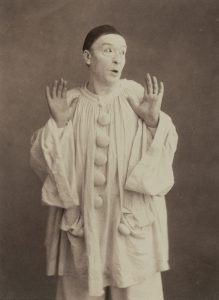

While reading “The Truth About What Happened” by Lee Child, there were a few things that popped out at me (especially after reading “Soir Bleu” right before it). Some of these were very obvious, such as the author’s choice to use dialogue for the primary structure of the piece, but there were other details and interpretations that I personally experienced and would like to point out. “Soir Bleu” is told through the perspective of the beret-clad artist, Vachon. He observes his surroundings in a pessimistic manner, chiefly his model, Solange, whom he claims as his Muse. Vachon exhibits intense egotism throughout the story, boasting that Solange has ‘fallen deeply in love with his genius’ and that ‘she no longer exists except by my hand.’ The latter gives indication of an inferiority complex that only solidifies throughout the story through his controlling attitude towards Solange and territoriality against other men.

“Soir Bleu” is told through the perspective of the beret-clad artist, Vachon. He observes his surroundings in a pessimistic manner, chiefly his model, Solange, whom he claims as his Muse. Vachon exhibits intense egotism throughout the story, boasting that Solange has ‘fallen deeply in love with his genius’ and that ‘she no longer exists except by my hand.’ The latter gives indication of an inferiority complex that only solidifies throughout the story through his controlling attitude towards Solange and territoriality against other men.

us how to construct the perfect interview via his “three second method.” On the very first page he states: “My answers were brief and concise. My control was good. I said nothing I shouldn’t have said. I used an old trick someone taught me long ago, which was to count to three in my head before replying to a question.” The purpose of this story is to prove that this method does indeed work and it provides us with a positive example for proof. If this story wasn’t mostly composed of dialogue, we wouldn’t be able to see how this interview goes right or wrong, we’d just have to take the narrator’s word for it.

us how to construct the perfect interview via his “three second method.” On the very first page he states: “My answers were brief and concise. My control was good. I said nothing I shouldn’t have said. I used an old trick someone taught me long ago, which was to count to three in my head before replying to a question.” The purpose of this story is to prove that this method does indeed work and it provides us with a positive example for proof. If this story wasn’t mostly composed of dialogue, we wouldn’t be able to see how this interview goes right or wrong, we’d just have to take the narrator’s word for it. hirtsleeves above his elbows. That angry vein in his forearm…”

hirtsleeves above his elbows. That angry vein in his forearm…” While I was initially taken aback by the drawn out sentences and near lack of punctuation, Ray Bradbury’s short story really intrigued me at its end. We learn throughout the story that our protagonist, George Smith, is quite the dreamer and often in his own head. Alice Smith, his wife, is quite the opposite. I’d even debate calling her the realist of the story, the grounding. As I’m sure others can agree, the ironic twist at the final act of the story was endearing as an outsider looking in, though I’m sure for George it was surely overwhelming. Meeting his favorite artist on the beach by sheer happenstance while getting to see him at work no less, sketching in the sand. What I loved most about this story in particular was the ending. The set of dialogue between George and his wife about what had just happened to him:

While I was initially taken aback by the drawn out sentences and near lack of punctuation, Ray Bradbury’s short story really intrigued me at its end. We learn throughout the story that our protagonist, George Smith, is quite the dreamer and often in his own head. Alice Smith, his wife, is quite the opposite. I’d even debate calling her the realist of the story, the grounding. As I’m sure others can agree, the ironic twist at the final act of the story was endearing as an outsider looking in, though I’m sure for George it was surely overwhelming. Meeting his favorite artist on the beach by sheer happenstance while getting to see him at work no less, sketching in the sand. What I loved most about this story in particular was the ending. The set of dialogue between George and his wife about what had just happened to him: The story that I decided to write about this week is “In A Season Of Calm Weather” by Ray Bradbury. In this story Bradbury creates the character of George Smith who is an avid lover of art, but mainly of the artist Picasso. George seems to see the world through Picasso’s eyes which, in my opinion, is an interesting way of perceiving things since Picasso is widely known for his abstract art. Bradbury takes the experience of George going on what is supposed to be a relaxing vacation and time spent between him and his wife and turns it into the way a man has been captivated by art and the artist and how he applies it to the real world.

The story that I decided to write about this week is “In A Season Of Calm Weather” by Ray Bradbury. In this story Bradbury creates the character of George Smith who is an avid lover of art, but mainly of the artist Picasso. George seems to see the world through Picasso’s eyes which, in my opinion, is an interesting way of perceiving things since Picasso is widely known for his abstract art. Bradbury takes the experience of George going on what is supposed to be a relaxing vacation and time spent between him and his wife and turns it into the way a man has been captivated by art and the artist and how he applies it to the real world.