“For fifteen years, Gregorio Aruna worked among us, building his museum of miniatures here in our village of Monterojo, high in the Sierras de las Marinas, and in all that time, no one was allowed in the door of his museum.”

As we navigate the introduction of Carrie Brown’s “Miniature Man,” we are led to believe that the inhabitants of Gregorio’s museum are untouchable; unreachable – and perhaps they are in a way. His craft is of personal intentions, and his work reflects the life he has conducted, one of self-inflicted solitude, or so we are initially led to believe. And furthermore, as the narration progresses and we tentatively unearth a fragmented storyline told from the perspective of an unreliable narrator, we are directed to perceive specific characters in a very specific way. The knowledgeable and wise doctor, Dr. Tomas Xavia. The attentive and doting mother Celeste. The placid and aloof father Carlos. And of course, the idiotic and idealistic fool, Gregorio.

As though to lighten the burden of being wrong, the blame is pointed towards Gregorio, because it is much easier to fault the person who seemingly created their own troubles, rather than acknowledges the lack of attention and awareness for someone who had been holding out for the appreciation of the ones he cherished most, the ones who were inherently his hardest critics, toughest antagonists, and perhaps even his greatest motivators.

It took the complete mutilation of his hands, his singular ability to create his work, for them to notice. Only when he became reliant on their aid were they finally able to notice him, as though for the first time. The work he’d been devoted to for decades and could no longer attend to was finally opened up to an audience that was too close-minded to realize they all were Gregorio’s incentive that spurred him on. His home and family; two things that attempted to break his spirit and ambition, just as the slab of marble broke his hands.

In a dream, Xavia receives the solution to what can be determined as the main conflict of the story.

“I dreamed of Gregorio’s museum, and I seemed to see it all as though I were a child passing slowly before the displays.”

Perhaps the weight of disregarded guilt manifested in his unconscious mind. Celeste then inquires what he believes the museum holds, finally showcasing some level of interest in Gregorio’s work.

“I thought of my dream. ‘Both familiar and strange,’ I said after a minute.”

Xavia then decides to organize an event for the miniaturist and his family to see a video filmed by Gregorio’s nephew of the undiscovered museum following a second dream. Those closest to him could be defined as practical and logical thinkers, so it comes as no surprise that it would be his own artistic nephew, acting as a vessel for the exposure of his work, who is able to finally bring Gregorio’s art into their household.

Even then, the rejoicing of his family once they witness his work feels hollow. On the surface level, the ending of the story seems to convey an atmosphere of joy, yet we can’t help but feel that this gratitude has been long delayed and has grown stale. What does it mean to Gregorio, who can no longer continue this work that they now so wildly praise? It falls flat. It’s not enough. His art was always talented, long before his accident. But it took the dismantling of his life for his family to finally recognize this, and it’s too late.

“There were two doors into this house. The first, in a small unfurnished room, opened directly onto the sea. It could only be entered from the water.”

“There were two doors into this house. The first, in a small unfurnished room, opened directly onto the sea. It could only be entered from the water.” “Passing by the room that opened onto the sea, she saw that the door was closed. She turned off the lights and locked up the house and walked down the stone path.”

“Passing by the room that opened onto the sea, she saw that the door was closed. She turned off the lights and locked up the house and walked down the stone path.” o the significance of vision becomes a pivotal key point and consistent theme throughout the short novel. This extends not only to the ideals of artistic vision but as well as the multiple concepts of sight, physically and metaphorically. This is delved into as early as the very beginning of the novel when we learn that Griet’s father loses his sight in a kiln incident after having been a prominent tile painter that previously had awarded him a position in an artistic guild. His blindness introduces us to the interchanging relationship connecting both vision and the loss of sight to each other, as well as the exploration into what we wish to see and what we turn a blind eye to, and the eventual repercussions of these actions.

o the significance of vision becomes a pivotal key point and consistent theme throughout the short novel. This extends not only to the ideals of artistic vision but as well as the multiple concepts of sight, physically and metaphorically. This is delved into as early as the very beginning of the novel when we learn that Griet’s father loses his sight in a kiln incident after having been a prominent tile painter that previously had awarded him a position in an artistic guild. His blindness introduces us to the interchanging relationship connecting both vision and the loss of sight to each other, as well as the exploration into what we wish to see and what we turn a blind eye to, and the eventual repercussions of these actions. g “two families now and they must not mix.” As this idea sets in, and she finds herself drifting from her home life to be fully emerged within Vermeer’s, her own familial ties begin to loosen, and eventually her own moral convictions follow suit. This deterioration is due, in part, to her growing infatuation with Johannes Vermeer himself. This blindness to her own identity and status allows her to sacrifice her morals without truly understanding the weight of the repercussions until it’s almost too late. But she is unable to alter it, because of the emotional and societal power imbalance in place.

g “two families now and they must not mix.” As this idea sets in, and she finds herself drifting from her home life to be fully emerged within Vermeer’s, her own familial ties begin to loosen, and eventually her own moral convictions follow suit. This deterioration is due, in part, to her growing infatuation with Johannes Vermeer himself. This blindness to her own identity and status allows her to sacrifice her morals without truly understanding the weight of the repercussions until it’s almost too late. But she is unable to alter it, because of the emotional and societal power imbalance in place.

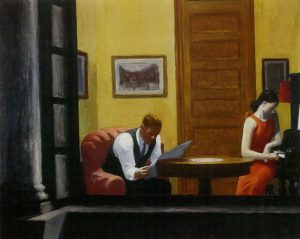

This short story, based on Edward Hopper’s most famous work by the same name

This short story, based on Edward Hopper’s most famous work by the same name